Archive

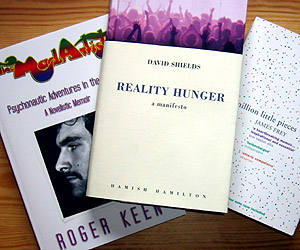

Mad Art and Reality Hunger

It’s always heartening to discover another writer who, perhaps by taking a very different path, has nonetheless arrived at a very similar creative place to oneself. This happened when I saw David Shields being interviewed on a BBC arts programme about his book Reality Hunger and the broader implications of the concept. He talked about the impoverishment of traditional fictional techniques and how today’s writers are incorporating more and more ‘reality’—that is, what really happened as opposed to what they made up—into their work. There is, he reckoned, a larger ‘reality hunger’ out there, manifesting in other media, such as reality television and the less adorned, more immediate communication afforded by the internet. Listening to Shields, I thought: that could be me talking, and I was amused by the discussion session following the film insert, where several panel members disagreed with him.

It’s always heartening to discover another writer who, perhaps by taking a very different path, has nonetheless arrived at a very similar creative place to oneself. This happened when I saw David Shields being interviewed on a BBC arts programme about his book Reality Hunger and the broader implications of the concept. He talked about the impoverishment of traditional fictional techniques and how today’s writers are incorporating more and more ‘reality’—that is, what really happened as opposed to what they made up—into their work. There is, he reckoned, a larger ‘reality hunger’ out there, manifesting in other media, such as reality television and the less adorned, more immediate communication afforded by the internet. Listening to Shields, I thought: that could be me talking, and I was amused by the discussion session following the film insert, where several panel members disagreed with him.

So I approached the book Reality Hunger with considerable excitement, while at the same time anticipating some mild disappointment due to my high expectations. But I wasn’t at all disappointed: the book proved to be everything I had hoped it would. It’s subtitled ‘a manifesto’, and it takes the form of numbered sections of varying lengths, which each have an aphoristic or epigrammatic quality. Many of the shorter ones are actual quotes from a wide range of writers and other artists, which Shields, acting like a DJ or MC, ‘samples’ and incorporates into the overall ‘mashup’. It is very effective and underscores the book’s textual points in a textural way, much like a plastic work of art. And as for the accusation of plagiarism, he answers that in the form of a quote from Picasso: art is theft. Who can argue?

As a drug memoirist, I had a special interest because I knew from the interview that this is an area Shields touches upon, and to my mind drug writing is an important component in the spectrum of this push toward ‘reality’. Indeed he mentions the Vedas—citing them as the earliest examples of written storytelling—and also De Quincey, Burroughs and Hunter S. Thompson before getting stuck into James Frey and his infamous tome A Million Little Pieces. Here is one of the finest examples of an ideological clash between ‘reality’ and ‘fiction’ in a contemporary book. Telling the story of a hopeless, burnt-out, twenty-three-year-old drug addict, who mends himself in a rehab centre, Frey firstly wrote the book as a novel, and when he had no success at marketing it, he rebranded it as memoir, after which it was outstandingly successful, selling in the millions.

Around three years after its first publication, details emerged of falsifications within the book, primarily that Frey had greatly exaggerated his criminal past, creating jail time that didn’t actually exist. This put his publisher in an embarrassing position, regarding the definition of ‘non-fiction’ and opened up a debate on the latitude of factual reportage within memoirs. It reached a climax when Frey and his publisher appeared on the Oprah Winfrey show and the result was a public crucifixion for the heresy of daring to place lies into a so-called work of fact. Afterwards Frey was dropped by his agent, and his publishers made him insert an apology into future editions. Past readers were even offered a refund, such was the furore the incident created.

As reported in Reality Hunger: ‘Oprah has created around herself a “cult of confession” that offers only one prix-fixe menu to those who enter her world. First the teasing crudités of the situation, sin or sorrow hinted at. The entrée is the deep confession or revelation. Next, a palate-cleaning sorbet of regret and repentance, the delicious forgiveness served by Oprah herself on behalf of all humanity… I’m disappointed not that Frey is a liar but that he isn’t a better one. He should have said, Everyone who writes about himself is a liar. I created a person meaner, funnier, more filled with life than I could ever be.’

Oh, that rings so many bells. Having written about my twenty- to twenty-four-year-old self in The Mad Artist, I discovered that however much you try to stick to the truth or the facts, you cannot help but turn yourself and others into ‘characters’, and characters start to assume a destiny of their own on the page. For me the writing of a ‘novelistic memoir’ was both an act of serving up reality and one of full literary performance at the same time. Read more…