The Cult of the Novel

A Literary Context For Contemporary Entheogenic Visionary Experience

What do you do if you’ve undergone a profound, like-changing mystical revelation and you want to articulate it in a way that’s workable, comprehensible and will make people take you seriously and not simply dismiss you as a headcase? Unless you already have an appropriate platform in place, it’s not an easy one. Within evangelical churches, most everybody is a visionary and their visions have a uniformity of focus and topic. Outside of such accepted institutionalised frameworks, highly vocal ‘visionaries’, perhaps infected with manic zeal—that certainty that the whole outside world must be automatically tuned into your special wavelength—and publicly acting out accordingly, might well find themselves being dealt with under the Mental Health Act. Labelling religious zealots as ‘lunatics’ has proved doubly convenient for societies throughout the ages, since the visions can be written off as ravings and the subjects can, if needs be, contained through incarceration, medication or both. And if the visions happen to be drug induced, then this is an even greater reason for their rejection by the world at large.

In the autumn of 1979 I underwent a three-week epiphany, an elevation into a higher, cosmically connected visionary space as a result of two medium-dose psilocybin mushroom trips taken close together. I imposed a Zen Buddhist, neoshamanistic context on the experience, as they were my preoccupations at the time. So in those terms I had achieved satori, become enlightened, attained a foothold in Ultimate Reality, which was the same as ordinary reality since the Cosmos had become an undifferentiated whole. In a more conventionally religious context, I could be said to have ‘found God’. Looking at the state from a psychological perspective, it was anything but ‘psychotic’, in fact quite the opposite, being super-connected, high functioning, exuberant, ecstatic. In this it had something in common with mania and hypomania, though it never tipped into the delusion, irrationality and destructive behaviour that often accompany true bipolar disorder. Though I was extraordinarily, superlatively high—‘on top of the world’—I hadn’t relinquished the frame of my ordinary life and in myself I felt basically healthy.

As a student of Zen, I knew full well that any description of an ineffable, transcendental experience could only ever be that—a description, not the experience itself: the Tao that can be spoken of is not the constant Tao. Yet it is human nature to communicate, to share, and in the case of the ineffable, to find new and better means by which something of that flavour of ineffability might rub off. At the time I was twenty-four and had just completed four years at art college, so when it came to choosing a suitable vehicle, I naturally turned to art, more specifically literary art, more specifically still metafiction—the use of self-referentiality to expand the impact of a text, with the further irony that the ‘fiction’ would be replaced by actuality, unembellished real-life events. This inspiration for ‘The Novel’ came to me early on in the second mushroom trip: it would celebrate my actions as an enlightened being, and at the same time would tell of the steps I’d taken to reach this exalted state:

‘And because I was aware that everything I did would be recorded, I would strive to make it as interesting and dynamic and ‘novelistic’ as possible! In fact, as an enlightened being, everything I did would be filled with excellence—it didn’t matter what I did! Everything in the butcher’s shop is the best!’

Shortly after that moment, my inspiration expanded to encompass ‘The Cult of the Novel’: ‘I envisaged a body of people hearing about my developing Novel, tuning into the message of my enlightenment and following my example, perhaps taking mushrooms and commencing novels of their own—reality novels, about what they were doing, not fabricated nonsense. They in turn would pass on the message to others and the whole thing would propagate far and wide, eventually spreading all over the world in the manner of a chain letter or a pyramid selling scheme. Disciples of the Cult of the Novel would spring up everywhere, all of them writing and reaching enlightenment as a result.’

It seemed as though I had all the answers and the momentum of my newfound world-conquering mission didn’t diminish after the mushroom effects had worn off. I saw myself as a ‘mad artist’, an alchemist in the field of postmodern literary reification, and I appreciated the fact that so-called ‘madness’ within the field of art carries a certain legitimacy. Artists have more latitude here, and being eccentric, just a little mad, goes with the territory—especially if accompanied by a degree of showmanship, such as in the case of everyone’s favourite erect-moustached surrealist Salvador Dali. A Mad Artist can have his say and be listened to, perhaps, in something like the manner of the shaman, and if a cult of self-sustaining novel-life could come out of it, encouraging other to share in the vision, then all well and good

So, for the next few weeks I involved my friends in my wild overarching ideas for potential real-life plots and narrative continuums, and then I gradually came back down to earth with a soft landing and got on with the rest of my life. The Novel was never completed; in fact it never got beyond the stage of being a collection of fragments. But then in many ways it wasn’t a novel to be written, but one to be lived. Thirty years later I returned to those years in my memoir The Mad Artist: Psychonautic Adventures in the 1970s, which adds a further meta-layer to it all—the non-fiction overview of the ‘fictionless fiction’ or ‘reality novel’, call it what you will. Constantly the book makes great play on the permeability of the membrane between real life and fictionalised or novelised real life—the Kerouacian roman à clef—and by extension the whole idea of myth and how it grows through progressive mutation and embellishment into something evidently no longer ‘real life’.

Now, when I look back at those events, what still stands up for me is the purity of the idea of ‘living a novel’, embodying that special bemushroomed perspective where life is a charmed adventure and everything is imbued with prismatic significance, together with the happy notion that this view can be passed on, extrapolated into The Cult of the Novel, wherein others can also experience life as a novel—epic, resonant, meaningful and divinely plotted in a way that transcends the strictures of the everyday, whilst being part of the everyday: the state of being, in the words of D. T. Suzuki, about two inches off the ground.

Please join in the discussion either here or on Facebook:

The Mad Artist

Promote your Page too

Image: ‘oracle’ by you are your atman on Flickr, courtesy of Creative Commons Licensing.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

‘Man of Letters’

LSD-inspired photomontage described in Chapter 17 of The Mad Artist

Pages

Recent Posts

Categories

- Blu-ray Writings (2)

- Book Excerpts (5)

- Cinema (18)

- Drug-Lit Classics (2)

- General Drug Lit (13)

- General Literature (17)

- Interviews (7)

- Literary Stalker (24)

- Man of Letters (1)

- Metacrime (18)

- Psychedelic Literature (30)

- Psychology & Psychotherapy (7)

- Short Films (3)

- Social Media (1)

- Talks & Conferences (2)

- Television (1)

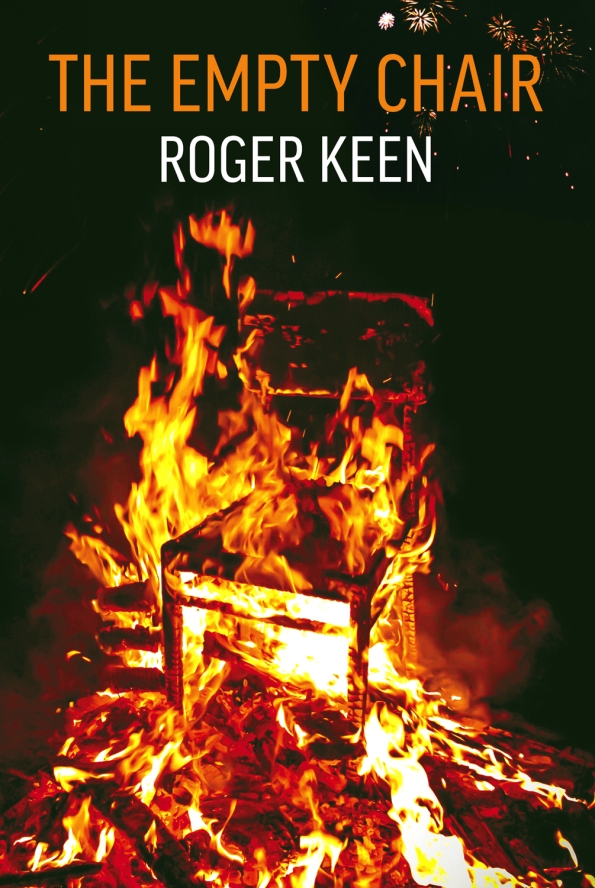

- The Empty Chair (5)

- The Mad Artist (17)

- Triskaidekaphobia (1)

Archives

- August 2023

- July 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- October 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- August 2021

- May 2020

- February 2020

- August 2019

- July 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- August 2017

- March 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- April 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- September 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- January 2013

- September 2012

- July 2012

- February 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- March 2011

- December 2010

- October 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

actually, just because something is fiction doesn’t mean it’s “fabricated nonsense”. Fiction is the physical form of our dreams and ideas, of things not currently in existance in this physical reality but no less real just because they’re not corporeal

And it’s worth considering that,under certain circumstnces, a fictional construct can be more real(for good or ill) than many non-fictional ones. How many folks’ lives have been effected by Don Quixote or Frodo Baggins or Luke Skywalker?

Living your novel is an interesting concept(though I don’t really feel the need for psychotropics to connect with Source or have a less than ordinary life). That being said, I’d say looking down on fictional reality misses something potentially important and transformational.

Wishing you all of the stories your life desires

Catherine

Foresight

Thanks for your comment, Catherine. The term ‘fabricated nonsense’ is a quote from the thought stream of the moment, and in no way is it intended as a denigration of the art of fiction generally, of which I have the highest respect and agree with what you say, but merely in that particular context to contrast the richness of the ‘real experience’ I was having against the relatively paucity of any kind of invented substitute. The eternal problem one has when trying to communicate ‘the ineffable’ is that the language one chooses is open to other interpretations. But hey, good to have a lively discussion about it!

Interesting article. I’ve actually had a similar experience and a novel was my answer to it as well. I’ve started to write it but it’s been a couple years since my experience and I’ve felt uninspired about it lately.

That was exactly my problem. After the initial euphoria had worn off, it was hard to maintain momentum. It took me over twenty-five years to come full circle and finally assimilate the experience—or the first part of it—in my memoir. Good luck with yours!

similar situation, similar experience, similar inspiration for a novel… and similarly, it has mostly worn off, although i still can feel the cloud of inspiration, waiting for me to give it my full attention, so perhaps one day…

When I was younger I used to document all my experiences in diaries and travel logs which together would constitute a narrative like a novel. However the effort of writing about things that are no longer so ‘novel’ as they were when I was young is no longer driven by the excitement of those new experiences. So perhaps the ‘Cult of the Novel’ would only really appeal to the younger generation who are experiencing life anew?

Thanks a ton for taking some time in order to compose “The

Cult of the Novel � Musings of the Mad Artist”.

Thanks a ton once more ,Sal