Archive

The Singing Detective and other BBC Classic Dramas

To celebrate its centenary year, the BBC has been airing reruns of many of its best and most-loved classic dramas on BBC Four. My favourites are Boys from The Blackstuff, Our Friends in The North, House of Cards and, of course, The Singing Detective. There is something warm and fuzzy about watching these works, from what has now in the 2020s become a ‘bygone age’. They’re all in colour, yes, but the 4:3 screen ratio, leaving big black side borders on today’s televisions, and the somewhat grainy and not very high resolution 16mm film, lend an archaic atmosphere that is nonetheless counterbalanced by sweet nostalgia.

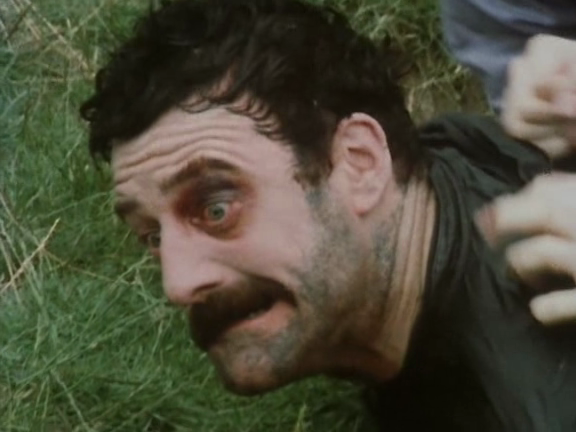

What has come over from the rewatching, personally, is how much these dramas mean to me and how they have influenced my writing. Take the episode Yosser’s Story in Boys from The Blackstuff, which shows the unemployed and unstable eponymous character in the throes of an existential crisis, leading to him becoming totally unhinged. Bernard Hill’s peerless performance got everything just right – the frustration, the sense of victimhood, the self-pity, and the crazy fulminating anger – so much so that back in 1982 he reminded me all too clearly of my own father, when he got into those kinds of moods.

Four years later, when I commenced my novel about a bad father, The Empty Chair, Yosser became a prototype for various versions of the bad father character, and when the film-within-the-novel develops, it is an older Bernard Hill who is cast to play that screen father.

Similarly, The Singing Detective, first broadcast in 1986, the very year The Empty Chair narrative commences, became a kind of ongoing parallel story. Its progression through misanthropy, psychosomatic illness, analysis of childhood, psychotherapy and the act of writing itself, mirrored everything in my novel. And when filmmaker Steve Penhaligon reaches the final stages of realising his film about his life, it is The Singing Detective’s mimed song-and-dance routines that unlock his idea to do the same with prog rock – King Crimson’s ‘21st Century Schizoid Man’ and Jethro Tull’s ‘Living in the Past’ to name two of the tracks.

In view of The Singing Detective’s rerun, I have republished a review I did for The Digital Fix from about ten years ago: The Singing Detective: The Triumph of the Invented Self

Review: To Fathom Hell or Soar Angelic by Ben Sessa

Author Ben Sessa is a psychiatrist, and his novel starts with a psychiatrist character, Dr Robert Austell, having a violent fantasy where he cuts a patient’s throat with a scalpel and nonchalantly watches her bleed to death. The reader can be forgiven for momentarily wandering just how autobiographical the work is, and indeed whether such things are the norm within the psychiatric profession! But of course this slasher opening is a piece of black comedy in order to set up the jaded, disillusioned Austell as someone who – like the majority of the working population – is bored with his job and wishes he could be doing something more enlightening.

Author Ben Sessa is a psychiatrist, and his novel starts with a psychiatrist character, Dr Robert Austell, having a violent fantasy where he cuts a patient’s throat with a scalpel and nonchalantly watches her bleed to death. The reader can be forgiven for momentarily wandering just how autobiographical the work is, and indeed whether such things are the norm within the psychiatric profession! But of course this slasher opening is a piece of black comedy in order to set up the jaded, disillusioned Austell as someone who – like the majority of the working population – is bored with his job and wishes he could be doing something more enlightening.

Austell’s situation is contrasted with that of another British psychiatrist, Dr Joseph Langley, who is living the New Age life in California, taking in the ocean vibes whilst high on LSD, his ego and self frittering away ‘into nothing but a river of effervescent specks of infinite light.’ Steeped in the alternative society since embryohood, Langley has brought those values to bear on his psychiatric work, and is now a renowned leader in the field of psychedelic therapy – using LSD, psilocybin, ketamine and MDMA to effect healing on the emotionally damaged.

The two psychiatrists come together when Austell happens to attend a psychedelic conference in California, not really aware of what he’s getting into. Here, the novel’s comic undertone gets a boost as a number of New Age weirdos are seen through Austell’s eyes. They include one speaker, Mountain Spirit, who sports a grey ponytail and talks of:

‘…The double helix gliss-openings percolating into our grid cubes transmit to us from mutated cadence entities. Using a synesthetic code derived from two-dimensional forms we exist simultaneously in identical universes. We jump in real time using fractal wave structures between this, our everyday world and the Other – where nothingness is connected with ourselves, the spirits and our environment.’

Austell thinks he’s a suitable case for sectioning, but as the conference progressives he becomes less judgemental of the quirks of psychedelic medicine, and by the time Joseph Langley speaks, Austell is more receptive. The two psychiatrists meet in the bar afterwards and begin a beautiful friendship, each seeing the other as their own flipside or complementary element in a yin/yang dynamic – Austell the down-to-earth jobbing physician with regular patient contact, and Langley the head-in-the-clouds world-changer who needs to get more pragmatic to achieve results.

They form a partnership, which leads them to establish a psychedelic medicine centre, down on a muddy farm in Somerset. Here, a selection of Austell’s patients – hopeless cases as far as conventional psychiatry is concerned – have their lives turned around and are completely rebased as a result of targeted treatment with LSD, psilocybin, ketamine and MDMA. Eventually a thriving commune develops on the farm, and word of the miracles being worked spreads far and wide.

Psychedelic medicine is Ben Sessa’s own pet project within his psychiatric work, and in To Fathom Hell or Soar Angelic, he is actualising a dream of it becoming generally accepted and even taking over the world. In reality it could never be as simple as portrayed, and no one knows this better than Dr Sessa himself, who has written and talked extensively about the obstacles, misunderstandings and general resistance there is toward such a venture.

But within sections of the psychiatric world itself, there is interest and sympathy for the clinical use of psychedelics, and this is something he wants to nurture. A novel, then, concerning the subject – with a far greater latitude of creative freedom than a non-fiction work provides – would seem like an ideal venture and a way to win over more support and attention regarding the cause.

But still, it has to be entertaining and page-turning to succeed, and indeed it does. Dr Sessa displays a great talent for creative writing and never ‘lectures’ his readers in a dull or pedantic way. Instead he uses irony and satire in liberal doses to take amusing sideswipes at conventional psychiatry – in particular its reliance on fat-profit pharmaceuticals to achieve any end. Whether it be benzodiazepines, SSRIs, tricyclics, anti-convulsants or antipsychotics, their efficacy is limited and patients really need something more to fill the black holes inside themselves.

Ben Sessa is also good at bringing characters alive, from spaced-out hippies to plodding psychiatric journeymen to burnt out headcases. His novel moves along rip-roaringly and leaves a constant smile on the face. Perhaps the story does involve a lot of wishful thinking, but that’s what psychedelic transformation is all about – dreaming wonderful dreams, attempting to make the impossible come true, and whatever the outcome it matters no great deal, for as the Buddhists say: the passing is nirvana.

To purchase a copy of the novel, please visit the Psypress Shop.

OCD & Schrödinger’s Cat

This is the first of several pieces I’ve lined up for the Medium site, which will have a wider remit than the film-and-lit focus of this blog, covering issues such as psychology and psychotherapy, self-help and advice, social media and promotion, and whatever else may come to mind.

This is the first of several pieces I’ve lined up for the Medium site, which will have a wider remit than the film-and-lit focus of this blog, covering issues such as psychology and psychotherapy, self-help and advice, social media and promotion, and whatever else may come to mind.

I got the idea for this piece whilst browsing articles on quantum mechanics and thinking about the paradoxical nature of much in everyday life…

I have a friend whom I shall call Brian who suffers from obsessive-checking syndrome. He will stare at a water tap or an electrical switch for minutes on end and then break away, only to return and repeat the exercise. He will slam his front door and then press it once, twice, three, four times and then break away, only to return and repeat the exercise. He will do circuits of his parked car, pulling on the door handles whilst angling his head to look and make sure the interior lights are off, and then break away… Yeah, yeah, you get the idea.

To someone witnessing this behaviour – and Brian’s neighbours have sometimes wryly commented on the floorshow – it appears ludicrous, comical and potty. Anyone might check something once, twice or even three times just to make sure, but after that it’s axiomatic that the situation is in an okay state. When I watch Brian I have to suppress a chuckle, and I remain perpetually amused and a little awestruck as I shake my head in pity, even though I’ve seen the show hundreds of times before. The trouble is, I suffer from obsessive-checking syndrome myself – though not nearly so badly as Brian. No, no, not as bad as that, no way! And anyhow, it’s different when it’s you doing it.

Why do you keep on checking when you can see, obviously, that the tap or switch is off or the door is locked?

Yes, you know the tap is off. You don’t doubt that the tap is off. What you doubt is that you’ve properly perceived that the tap is off. And in consequence, if there is a possibility that your perception may be faulty, then there is also a possibility that the tap may not be off after all. That is why you constantly check – not to check that the tap is off, but to convince yourself that your senses are working correctly. And as you’re using your senses to monitor your senses, an element of double bind and infinite regression is inevitable. You just have to continue until you can make that leap of faith and be convinced and truncate the checking. Once you do reach that point you know you can remember the fact later for support, if and when doubts start to recur when you’re away from base. For some it’s harder than for others.

But why go through all that palaver? Why don’t you just accept the tap is off and leave it at that?

Well, if that were possible there wouldn’t be a problem – there wouldn’t be such a thing as OCD and we wouldn’t be having this conversation. The same is true for depression – if you could just ‘snap out of it’ or ‘pull yourself together’, every depressive would do that and depression would become a forgotten illness in about two seconds flat. But of course it doesn’t work like that… Read more on Medium

Film Review – The Substance: Albert Hofmann’s LSD

Originally published on The Digital Fix, here is my review of this excellent LSD documentary.

Review: Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? by Jeanette Winterson

Most misery memoirs are first books penned by people who are often not primarily writers, but who simply have extraordinary tales of woe to articulate. It is a very commercially-driven genre, where writing quality is not paramount, sometimes involving ghost writing; and it’s become a bandwagon that the ever expanding ranks of celebrities are wont to climb onto, as their names alone will sell books.

Most misery memoirs are first books penned by people who are often not primarily writers, but who simply have extraordinary tales of woe to articulate. It is a very commercially-driven genre, where writing quality is not paramount, sometimes involving ghost writing; and it’s become a bandwagon that the ever expanding ranks of celebrities are wont to climb onto, as their names alone will sell books.

This makes Jeanette Winterson a special case with Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? as she’s an established writer of long standing, and way back in her twenties she already addressed her turbulent and troublesome early experiences in her semi-autobiographical first novel Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit. So why revisit this territory and de-fictionalise it? Why re-clock the car to zero, so to speak?

It’s partly down to the changed perspective of middle age, where all becomes recast in a historical rather than an immediate context; and not only her own life but also her surroundings – Manchester and Accrington and their industrial heritage. She paints a picture that certainly supports the adage ‘it’s grim up North’, involving austere little houses with outside lavvies and no central heating or fridges or telephones. I am four years older than Jeanette, but as a southerner whose childhood was surrounded by ‘all mod cons’, hers feels like it belongs to an earlier generation.

Similarly she redrafts the almost 19th century figure of her stepmother, whom she refers to as ‘Mrs Winterson’ and who uses the matrix of her religious beliefs as an enabler of her abuse. Jeanette’s childhood involved corporal punishment, dished out by her father on the instructions of the dominant mother, nights spent of the front doorstep having been locked out of the house, and the burning of her hidden and forbidden book collection after it was unfortunately discovered.

Nevertheless Jeanette absorbed enough literature to get to Oxford to study English, become a successful writer and leave all that toxicity behind. But of course it’s never that simple. And so we come to what Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? is really all about – the spectre of unfinished business, the part of her story that serves as a corollary to Oranges. Read more…